EditorialWhy Ignorance Might Be the Most Valuable Skill of the AI Era

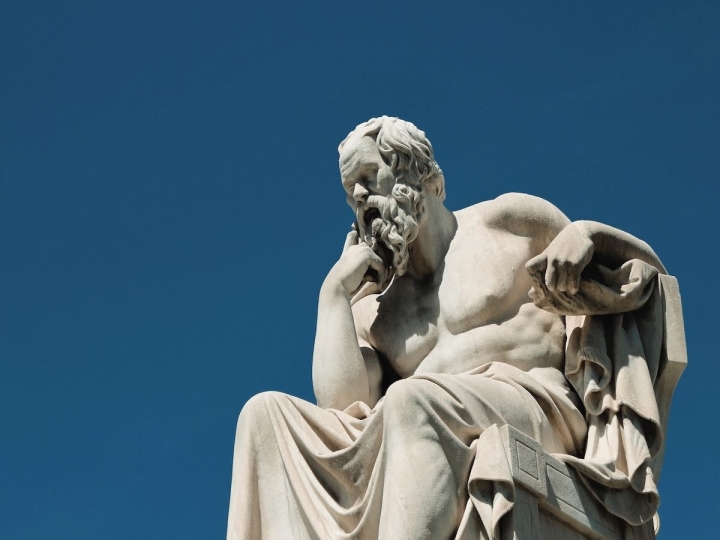

In 399 BCE, while on trial for “corrupting the youth,” Socrates told the Athenian jury, “I am likely to be wiser than he to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know” (Plato, "Apology"). In that moment, he offered not merely a defense, but a philosophy: true wisdom resides not in the accumulation of answers, but in the disciplined practice of acknowledging one’s ignorance. For centuries, this principle guided education, shaping it as a process of inquiry rather than a race toward certainty.

Simpler Media Group

Put simply, Socrates was saying, “I am wise because I know that I do not know.” He understood that genuine wisdom begins with recognizing our limits and refusing to pretend we possess knowledge we do not. For generations, education embraced this approach. We taught students to question, to probe uncertainty and to seek understanding rather than simply to recite information. Yet today, in an era where artificial intelligence delivers rapid, confident answers to nearly any question, the danger lies in replacing the habit of questioning with an uncritical acceptance of what is given.

In a world where innovation and creativity are indispensable for navigating an “it already changed again” technological society, the capacity to recognize and value one’s own ignorance may no longer be a philosophical ideal alone. It may be one of the most essential job skills of the future.

Why Struggle Matters: The Cognitive Cost of AI Convenience

Higher education has long wrestled with a performative culture in which students are trained to ask “What’s on the test?” rather than “Why does this matter?” Artificial intelligence supercharges this tendency.

A 2024 EDUCAUSE survey found that 54% of students now use generative AI weekly for academic work, with most seeking “direct answers” rather than guidance through reasoning. In one multi-university study, 76% of AI-assisted student queries focused on producing “perfect” answers for immediate submission rather than exploring underlying concepts.

This shift erodes what cognitive scientists refer to as desirable difficulties — the productive friction that deepens learning. According to Muis et al. (2021), certain forms of discomfort can be beneficial: confusion and anxiety, when experienced in manageable doses, strengthen critical thinking, while frustration tends to undermine it. Confusion can serve as a bridge between a learner’s beliefs about knowledge and their capacity for higher-order reasoning.

According to Greene and Yu (2016), such epistemic emotions are closely linked to how individuals evaluate evidence and engage in higher-order reasoning, making them essential to developing the capacity for critical thinking about complex issues. By bypassing the discomfort of grappling with complexity, students not only retain less but also weaken the metacognitive skills essential for adapting to unfamiliar challenges. Compounding the problem, AI platforms often reward this shortcutting; the more precise and high-stakes the user’s request (“Write me an A-level essay”), the more likely the system is to produce something polished yet pedagogically hollow.

What Happens When We Stop Asking Why

The danger is not merely intellectual laziness; it is the unlearning of inquiry itself. When artificial intelligence renders the process of discovery invisible, the how becomes irrelevant. If higher education becomes complicit in that erasure, it will produce graduates capable of executing tasks without understanding them, trading the art of thinking for the illusion of competence.

This risk emerges in a world where learners navigate an unprecedented volume of information, perspectives and claims on topics ranging from scientific debates to historical controversies. The ease of access to such a vast array of viewpoints has intensified calls for educational reform aimed at preparing students to participate thoughtfully in democratic society, succeed in the modern workforce and close performance gaps with international peers.

A recent MIT study on AI-supported self-explanations found that when AI reframed information as questions, prompting users to reason through the content rather than simply consume it, participants significantly improved their ability to identify flawed logic and were more inclined to seek additional evidence before forming conclusions. Meeting these demands requires more than mastering basic knowledge and skills; it demands the ability to think critically about complex and often contentious issues. Yet, as Greene and Yu argue, critical thinking is neither automatic nor easy to cultivate. It requires deliberate practice in evaluating competing perspectives, assessing evidence and navigating ambiguity.

Without such emphasis, students risk becoming proficient consumers of answers rather than active participants in the process of discovery — undermining the very purpose of higher education in the age of AI.

Moreover, the questions we pose to large language models today actively shape their future “intelligence.” Each query refines the machine’s capacity, building systems with the breadth of PhD-level knowledge. The knowledge seeded through questions once posed by human experts. In doing so, we risk outsourcing the development of thought itself, mining our collective intellectual labor to feed the machine and leaving ourselves content to seek answers rather than wrestle with ideas. Human genius, however, has always emerged not from the speed of an answer, but from the process, and often the struggle, of grappling with complexity, confronting uncertainty and shaping meaning through our own intellectual labor.

The Faculty Fear Factor: Teaching in the Age of AI

Faculty, too, are caught in AI’s confidence trap. The “sage on the stage” archetype, already under pressure from the shift to active learning, is now haunted by the specter of being corrected in real time by a chatbot. Instructors are aware that students can, within seconds, fact-check any statement or pull up alternative explanations. For some, this fuels avoidance: sticking to slides, speaking from scripts and steering clear of speculative or exploratory dialogue that could expose uncertainty.

Research on teaching presence in online learning shows that perceived instructor expertise strongly correlates with student satisfaction, but the inverse is also true: perceived uncertainty can damage credibility in environments where authority is conflated with correctness. When faculty fear that being wrong, rather than being unwilling to learn, is the greater sin, they retreat into safe, static delivery.

The irony is that such practices deprive students of the very modeling they require. Greene and Yu's look at epistemic cognition demonstrates that learners build resilience and critical thinking not through observing flawless performance, but through witnessing experts navigate ambiguity, confront errors and engage in self-correction. Recent findings from DeVries, Orona and Arum (2025) further reveal that faculty who openly display intellectual humility, by acknowledging gaps in their knowledge, inviting alternative viewpoints and modeling curiosity, positively influence students’ own willingness to engage in complex reasoning and question assumptions. In other words, the very behaviors some faculty fear will erode their authority are the ones most likely to strengthen students’ intellectual engagement.

When professors present themselves as infallible, or worse, outsource the performance of infallibility to AI, they perpetuate the myth that knowledge is static and beyond challenge. In the era of AI, higher education must redefine intellectual authority, shifting from “always being right” to “always being willing to ask why” and to venture further into “what if.”

Ignorance as a Critical Job Skill

The modern workplace is not a cathedral of certainties; it is a labyrinth of shifting variables. Artificial intelligence may excel at managing the “known knowns,” yet, as Gary Marcus and other AI critics contend, large language models remain brittle when confronted with unfamiliar contexts, especially those requiring moral reasoning, contextual sensitivity or the interpretation of incomplete data.

Employers increasingly identify adaptability, curiosity and critical thinking as the most sought-after competencies. Such skills are not cultivated through the passive absorption of ready-made answers, but through the disciplined engagement with uncertainty. As Plato records in "Apology," Socrates recognized that true wisdom begins with the admission, “I neither know nor think I know.”

Paradoxically, the ability to acknowledge and manage ignorance is now an employable skill. Studies in HBR on organizational learning demonstrate how “situational humility” enhances decision-making in volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environments. Likewise, research in medical education shows that physicians trained to articulate uncertainty and seek collaborative input commit fewer diagnostic errors. The same logic applies to graduates navigating AI-enhanced industries: those who can critically assess, contextualize and challenge algorithmic outputs will lead rather than follow.

In this sense, “ignorance” is not the absence of knowledge but the recognition of its limits — a cognitive posture that AI, for all its computational brilliance, cannot model. Machines do not admit when they lack certainty; they hallucinate, fabricate and present falsehoods with the same rhetorical confidence as truth. Higher education’s responsibility is to equip students to detect that gap, empowering them to see that the acknowledgment of not knowing is not weakness, but the starting point of inquiry.

Reclaiming Education’s Purpose in the Age of AI

To reclaim its purpose, higher education must resist the seduction of automated certainty and re-anchor itself in the philosophical tradition of questioning. This means:

- Making cognitive humility explicit: Embed epistemic humility as a learning outcome across curricula, assessing not only what students know but how they navigate what they do not know.

- Rebuilding inquiry-driven pedagogy: Use AI not as an answer engine but as a provocateur, design prompts and assignments that force students to interrogate the machine’s reasoning, biases and blind spots.

- Normalizing visible ignorance in teaching: Train faculty to model critical engagement with AI outputs, showing students how experts wrestle with incomplete or conflicting information.

As Socrates understood, the act of not knowing is not a void but a compass. In a world where AI will increasingly fill in every blank before we can wonder what belongs there, higher education must defend the pause, the question, the productive silence. Ignorance — honest, disciplined and relentlessly curious — is no longer a philosophical luxury. It is, perhaps, the most important job skill of the 21st century.